I also write with the intent to reach out to individuals who have suffocated their own inner flame by internalizing problems caused by bad management:

“Maybe I was just being too much of an idealist.” “Maybe I just haven’t grown up.” “I need to just manage my stress better.” I want to be the warmth of reassurance: It’s not that you’re just an idealist. It’s not that you haven’t grown up. It’s not that you just don’t know how to manage your stress better. It’s real. You’re real. I want to be the spark that rekindles your desire to do what you believe is right, and the updraft that raises your confidence to take the first step forward.

0 Comments

A few years ago, I spoke with someone who has decades of experience in organizational change management with the hopes that I can do something to change my organization. I had a few conversations, but nothing useful came out of them. In fact, I came out of those conversations feeling not only useless but worthless too.

I was faced with the cold reality that change management consulting is, in fact, a business. Change management consultants need revenue to make a living, so they need to choose their clients. Their clients are executives in the C-suite who have the authority to pay the consultants. So they cater their services to where the money is. As a result, the suggestions I got from the change management consultant were not applicable for me at all; they were for the C-suite executives. Building a business plan. Speaking to the board of directors. Budget. Finances. All I could say was "I don't know," or "I'm not in the position to do that." It felt like I shouldn't be a part of the change management conversation to begin with because I don't have any power. Are there people who are feeling useless like the way I did a few years ago? If yes, then how can I help them? What can I do to find them? How can I reach out? One of my answers to these questions (although not a complete answer by any means) was to write - to share my experiences and to not stay silent about the matters I care about, get angry about, feel guilty about. Someone may stumble across what I write and realize that they're not alone. Could it be you? This is an answer post to my previous piece on how someone's undesirable behavior could've been seen as a symptom of a larger-scale problem but it was dismissed as only that person's problem. I see this as an opportunity cost for the organization. The organization could have:

To properly address the cause of undesirable behavior in individuals and to get honest feedback about the organization, it is of utmost importance to make the person feel safe and relaxed (the person is probably on the verge of crumbling with anxiety). In doing so, there are a few things to take into consideration when soliciting authentic feedback:

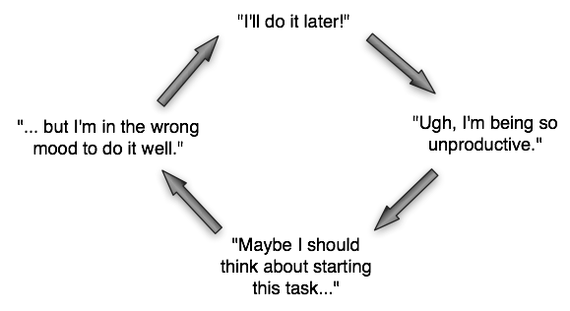

I'm sure I'm coming back to the "what do you do instead of blaming someone?" theme over and over again in future posts because blaming in the workplace happens way too often and to me, it ends up harming the organization as a whole as opposed to protecting it. Disclaimer: This post is not about “X ways to overcome procrastination” or “procrastination is actually good for you.” I choose to not to write about either topics because a) many people wrote about that already (there’s not much that I can add), and b) it’s usually about the individual, and I’d like to focus more on the impact it has on the organization. First, allow me to clarify what I mean by procrastination. Derek Thompson in “The Procrastination Doom Loop—and How to Break It” provided a great definition for procrastination so I will refer to that here: Productive people sometimes confuse the difference between reasonable delay and true procrastination. The former can be useful (“I’ll respond to this email when I have more time to write it”). The latter is, by definition, self-defeating (“I should respond to this email right now, and I have time, and my fingers are on the keys, and the Internet connection is perfectly strong, and nobody is asking me to do anything else, but I just … don’t … feel like it.”). Furthermore, in this context I will assume that the procrastinator is a high performer. For example: the person knows he/she is responsible for the work, knows how to prioritize and manage time well based on the priorities. If a high performer is chronically procrastinating despite the fact that he/she is very capable and perfectly aware of his/her responsibilities, I suspect that there is a much larger, ominous problem underlying the behavior. The lack of motivation. There are many ways a person can lack motivation, and it may not be that person’s fault. The person might not believe in why the work they’re responsible for is actually worthwhile doing. The person might not believe in why the task or role is delegated to him/her. The person could be suffering from clinical depression. Or burnout. It could be a combination (if not a myriad) of things. Some may think, “well… it doesn’t have to do with whether you’re motivated or not because what needs to get done needs to get done.” I find this view to be prevalent among both the people who tell procrastinating high performers to “just do it,” and the procrastinating high performers who drag their feet to get things done. But to me, it looks like sticking a band-aid on a swollen area that’s actually caused by a bone fracture. Let me tell you a story about a procrastinating high performer, and a handful of things that contributed to the procrastinating behavior (names have been changed due to privacy reasons). The story of a procrastinating high-performerMeet Judy. Judy is entirely self-driven. External motivation doesn’t mean much to her because her motivation is fully intrinsic. She finds joy in large-scale problem solving — looking at a complex problem from different facets and exploring the design space for building solutions. That’s one of the reasons why she co-founded a small data analytics/design consulting startup. Judy also happens to have some knowledge in managing finances and administration. Since she was involved in a startup (where one person typically needs to take on multiple roles because there’s not enough resources to hire people in each specialization), she ended up taking care of finance and administration in addition to domain-specific consulting work. Judy has ADD (attention deficit disorder). During a typical work day, she spends around 80% of her time and effort trying to focus, and so she doesn’t actually spend that much time actually executing. But since she is extremely efficient, she can produce high-caliber deliverables very quickly compared to the average performer. Keeping track of things is not her forte; she can do it but it requires tremendous effort and focus compared to an average person to get it done. For example, a seemingly simple task such as counting is a daunting task for Judy (imagine being constantly interrupted by everything around you while you try to count). Switching tasks is not good for her either, because she needs to spend a lot of time and cognitive energy to re-focus. Judy is also a perfectionist who battles anxiety and depression. She needs to put in a lot of conscious effort to not feel ashamed of herself. Keeping this in mind, let’s walk through what Judy experiences. Since Judy’s motivation is solely driven from solving analytical problems, she is extremely productive in her consulting work but not as much in the finances and administration. She has difficulty taking and keeping track of records, making precise calculations, figuring out why the numbers don’t match up, keeping track of deadlines, and even being motivated enough to complete things before the deadline. As a result, the financial and administrative tasks start to fall behind, and self-shame starts to rapidly accumulate (Judy is a perfectionist), and she is aware that it’s nearly impossible to do all the finances perfectly in addition to her consulting work. And the procrastination doom loop starts: Oftentimes, deadline setting strategies are mentioned in pieces that talk about procrastination, but in Judy’s case, deadlines — whether they are self-imposed (“I need to start on this by next week.”) or external (“I will get penalized if my submission is late!”) — do not influence her motivation. Judy does not have a good fit with her role. But you see... the problem does not stop there. It turns out that Judy was not in the right role, yet there was no one else who had a better fit for that role! Although Judy has problems keeping track of things, her teammates were even more disorganized than she was. There wasn’t the right mix of people running the organization: everyone in the organization was strong at one thing, and weak in the other. So the problem was actually systemic — it wasn’t only about Judy. Yet, Judy was the only one who was blamed for. Her inner flame was extinguished. She left the organization not too long after she got bombarded with a tirade by a "livid" (I'm using the word "livid" because that was the word used by the person delivering the tirade) colleague. When a problem sheds light on a larger-scale problemI can't stand to see one person's inner flame get extinguished as a result of a system's problem (they're getting all the blame for something that's not their fault)! It isn't fair.

This case study was an example of when a behavioral problem (like procrastination) could have shed light on a larger-scale organizational problem, but that never came to fruition because one individual was blamed for (and that person left). I believe that there is a way to actually address individual behavior problems so that the organization can gain insights about itself (and the systemic problems it may have). More on that in a later post. I need to take deep breaths for the next week or so to calm myself down. |

AuthorI'm Candice and I doodle with the intensity of the doomguy. Categories

All

Archives

March 2021

|